In October the Consumer Attorneys Association of Los Angeles, or CAALA, named Steve Vartazarian of The Vartazarian Law Firm as the plaintiff lawyer association’s 2019 Trial Lawyer of the Year, one of the most prestigious recognitions in the California legal community.

In a wide-ranging interview with Courtroom View Network, Vartazarian laid out his journey from a law school reject who bombed the LSAT to being listed among the most accomplished plaintiff attorneys in California, attributing his meteoric rise to a visceral disdain for low-ball settlement offers, regular use of pre-trial focus groups and good old-fashioned networking.

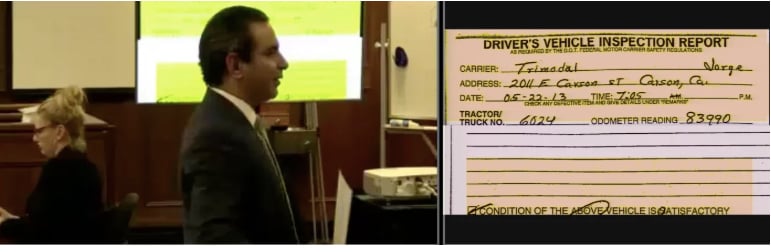

CVN screenshot of Steve Vartazarian in trial delivering a closing argument

Hearing Steve Vartazarian’s voice grow steadily louder on the phone as he recounts the first time he rejected a settlement offer he found insulting, it’s clear he’s still fired up about it.

As a young attorney just getting on his feet, he made a demand in a soft tissue injury case for $30,000. An insurance adjuster responded with an offer of $27,500.

Perplexed by the resistance over such a small amount, Vartazarian asked the adjustor why he wouldn’t just pay the $30,000.

“If you’re willing to take $30,000, you’ll take $27,500,” he remembers the adjustor telling him. “Who the hell would try a case over $2,500?”

“It was at that moment that my ‘F-U’ attitude was born,” Vartazarian stated proudly.

At the time Vartazarian and his wife, also an attorney, were just starting to bootstrap their own small operation, their living room cluttered with boxes of legal briefs and with barely enough money in the bank to cut their secretary her next paycheck.

“Later on I realized 90 percent of attorneys would have taken that offer,” Vartazarian, now 45, said. But at the time he seethed over a powerful insurance company arbitrarily trimming a payout simply because they could.

He took the case to trial with his client's blessing, rejecting a $50,000 policy limit offer before opening statements. The jury returned a $180,000 verdict, and after losing an appeal the insurer ultimately had to pay in excess of $230,000.

That outcome in a relatively small case set the theme for Vartazarian’s rapid development as a trial attorney. Case after case, he repeatedly brushed aside settlement offers - and the financial security they can bring - in favor of taking claims that he felt were meritorious before a jury and securing substantially larger jury verdicts.

“It doesn’t make business sense,” he concedes. “Not a lot of people think that’s wise because settlement puts money in your bank account so you can live.”

Acknowledging that many attorneys would shy away from the inherent uncertainty a jury trial presents when faced with a sure-thing settlement, Vartazarian says he mitigates that risk by only going the distance in cases he thinks sell themselves on the facts.

“We don’t jack up life care plans. We don’t create damages where they otherwise didn’t exist,” he said. “We just bring the black and white.”

It’s an approach that’s borne fruit, with enough multi-million dollar verdicts under his belt to land a spot just a decade after opening his own firm on an exclusive list with past CAALA Trial Lawyers of the Year and giants in the California plaintiff attorney community like Brian Panish, Thomas Girardi and Gary Dordick.

Among the cases in CVN’s online trial video library featuring Vartazarian are a $4.5 million verdict in a first-of-its-kind metal hip implant product liability lawsuit, an $11 million verdict awarded to a USC Medical Center employee run over by a forklift, and an $11 million verdict in a wrongful death/trucking accident trial.

And that’s just a sample of what Vartazarian’s “all-in” trial-focused litigation strategy yielded over the last decade.

When viewing the section of The Vartazarian Law Firm’s website listing notable case outcomes (the most recent being a $113 million result in a child abuse lawsuit against San Bernardino County) a pattern quickly becomes obvious - they’re all jury verdicts.

Most plaintiff firms highlight a mix of settlement and trial outcomes, but The Vartazarian Firm makes their wheelhouse clear. They go to trial.

Vartazarian does agree to settlements in cases with less favorable claims, but otherwise the driving force behind his work as a litigator is the unshakable faith that if the facts are truly on a plaintiff’s side, they’re almost always better off going to a jury with a capable trial lawyer than agreeing to a settlement.

That confidence in the face of the massive risk (and potential cost) of a jury trial begs the question: how is Vartazarian so sure a case has what it takes to yield a big verdict?

His answer is simple. Focus groups.

“How the hell do you try a case without focus grouping it first,” he asked incredulously. “That makes no sense to me. There is nothing more valuable than a focus group. Nothing.”

Vartazarian says he extensively focus groups the claims in every case he takes to trial. If another attorney asks him for advice on an upcoming trial, his first question is always, ”Have you focus grouped this case?”

He insists pre-trial focus groups should not be a tool utilized only by large, well-heeled firms with money to burn. He admits pricey jury consultants with PhD’s can play a role in developing trial strategy, but believes that for basic, real-world vetting of claims and damages before a simulated jury all you need is a conference room and some pizza.

CVN screenshot of Steve Vartazarian kneeling in front of a photograph of the type of forklift that ran over his client's legs

Vartazarian says he has access to a focus group pool through jury consultants he works with, and that he pays a $50 finders fee per participant. He runs a three-hour session from 6-9pm in his office (no fancy mock courtroom required), giving the opening statements for both sides and then questioning the mock jurors about what resonated with them.

Each session, pizza included, usually costs him between $1,900 and $2,200, an almost incidental amount in the larger scope of a complex trial. And it’s that relatively small investment that gives him the certainty to reject settlement offers that other plaintiff attorneys would likely take.

The previously mentioned trials involving Vartazarian in CVN’s video library are perfect examples, all involving substantial settlement offers but resulting in even larger verdicts.

In the metal hip implant case, the defendant’s highest pre-trial settlement offer was $455,000. Vartazarian’s demand was $4 million. The jury returned a $4.5 million verdict.

In the forklift injury case, Vartazarian rejected a $1.5 million settlement offer, increased to $5 million during jury deliberations. The jury returned an $11 million award.

And in the trucking crash trial from this past January, Vartazarian’s $11 million verdict beat out a $700,000 settlement offer.

By relying on focus groups so heavily, he says he’s limited his losses at trial to just two defense verdicts in the last five years.

Vartazarian admits taking this approach to advocacy is risky and in many ways unorthodox, but he says he’s eager to pass along what he knows to any younger attorney who wants to listen, noting that support for younger, up-and-coming attorneys is one of the greatest benefits of involvement in the CAALA community.

“I’m an open book,” Vartazarian says, noting he’s having dinner that night with a younger attorney who reached out for advice. “Anyone who is a CAALA member can come to my office and I will give them everything I have. All my connections. All my animations. All my pleadings. I’ll give them my time.”

While clearly generous with his advice, Vartazarian cautions that attorneys will be much more likely to give that advice if they’ve spoken to someone in a social setting, even for only a few minutes. He laments that so many younger lawyers don’t realize how important out-of-office networking can be for their professional development.

“I find that a lot of younger attorneys don’t do that. They go straight home,” he griped. “At 6pm if you’re a young attorney, don’t go home.”

Vartazarian cites events like CAALA-sponsored mixers as the ideal forums to make those initial connections.

“If you go to CAALA mixers long enough somebody is bound to like you,” he joked.

Stuart Zanville, CAALA’s Executive Director, told CVN that support for newer attorneys is one of the key goals of the 3,100-member organization.

“CAALA’s culture is highly supportive of younger members,” Zanville said. “The organization is unique among legal bar associations for providing members with so many opportunities to connect.”

He touted member benefits like seminars, social events, dedicated new lawyers and women’s programs, a vibrant email list, free access to Courtroom View Network, a document bank with more than 3,000 documents and CAALA’s popular annual convention, known as the “CAALA Gala.”. But echoing Vartazarian’s sentiments, he said none of that is more valuable than the networking opportunities CAALA provides.

“None of those resources are more beneficial for members than the ability to connect with other CAALA members,” he stressed.

Those connections literally made the difference for Vartazarian between keeping his head above water and not during the financial lean times that an almost exclusively trial-focused practice can create for a small firm that works on a contingency basis.

He recalls a period when he had multiple verdicts tied up in appeals, and says the only way he paid the bills was by taking on lucrative cases referred to him by Arash Homampour of The Homampour Law Firm, a prominent California plaintiff attorney and the 2009 CAALA Trial Lawyer of the Year. (Note: CVN will be webcasting one of Homampour’s trials starting later this month in San Diego.)

Further reinforcing the argument that being a “known entity” is critical for young lawyers, Homampour told CVN that the personal impression Vartazarian first made on him outside the courtroom him is what laid the groundwork for him to later support Vartazarian professionally.

“Early on, I first noticed him as a peer and not necessarily as a great litigator because he was doing difficult liability medical malpractice cases,” Homampour said. “But he and his wife had an amazing energy of love, sharing and being of service. I knew that who he was outside the courtroom would translate to one of the best in a courtroom.”

“Steve presents arguments in an easy to follow, passionate and compelling way,” Homampour continued. “He has the ability to take complex issues and make them very simple for jurors to understand. He also neutralizes and reverse choke-holds defendant’s bogus arguments in a way that is endearing.”

Homampour is right. Vartazarian is undeniably affable. Despite his self-characterized “F-U’ attitude towards insurance companies, he is best described as a ‘happy warrior.’

And It’s his likability that helped him get his foot in the door after law school while he showed up for work, week after week, at a law firm where he didn’t even have a job.

A California native, Vartazarian went to college in Oklahoma for a change of scenery. Looking to extend the collegiate lifestyle after graduation but lacking a stellar GPA, he pinned his hopes on a high LSAT score to land a spot in a top law school.

He scored a dismal 148.

“You can’t get into any school with that,” he recalls.

He received rejection letters from every school he applied to. To his surprise while visiting a friend out of state in the late summer he got a frantic call from his parents in California. The admissions office from the Thomas Jefferson School of Law in San Diego called his house asking if he knew he’d been admitted, their previous correspondence seemingly never arriving due to a glitch in the mail.

Vartazarian enrolled immediately and graduated with a GPA around 3.0, but coming from a lesser-known regional law school and not graduating near the top of his class, he found himself repeatedly turned away by every law firm he contacted.

Ready to ditch a legal career entirely and go into real estate development, Vartazarian in desperation reached out to his uncle who had worked as a parking attendant near a law firm’s office in the 1970’s. A lawyer he’d become friendly with and kept in touch, Jack Denove (CAALA’s 1993 Trial Attorney of the Year), had since become a named partner at the plaintiff firm Cheong Denove Rowell Bennett and Hapuarachy.

Denove agreed to hire his old friend’s nephew for a short-term temp assignment writing a research paper on benefit structures for accident victims. Sequestered alone in the firm’s dusty library, Vartazarian finished the assignment quickly. Meanwhile, a busy trial schedule kept Denove largely out of the office, so once Vartazarian’s initial assignment was finished he just kept showing up.

“I kept coming every day, even though I wasn’t getting paid,” he said, describing how a combination of a good work ethic and winning over the people in the office on a personal level resulted in a steadily increasing workload of small tasks like drafting initial demand letters and summarizing medical records.

Upon his return to the office, he remembered a shocked Denove exclaiming, “You’re still here?!”

“I admired his work ethic and hired him for an embarrassingly low salary,” Denove told CVN.

It’s a decision he’s proud of, as Vartazarian eventually became an associate at the firm and developed the skillset he’d need to eventually strike out on his own seven years later.

“What Steve does can’t be taught or imitated,” Denove said. “He is the real deal.”

Denove says the same likability and work ethic that convinced him to first hire Vartazarian is what gets jury after jury to award his clients multi-million dollar verdicts.

“By the time the trial starts Steve believes in the righteousness of his case and the jury can sense that,” Denove said. “He has a style of communicating with a jury that not only engages the jury but convinces the jury of his sincerity.”

But what truly sets Vartazarian apart from most trial attorneys according to Denove is his willingness to turn down settlement offers and put his client’s fate in the hands of a jury.

“He is willing (with his client’s consent) to turn down an offer that most attorneys would jump at so he has the opportunity use his hard work, his beliefs and his outside the box thinking to get the jury verdict he and his clients deserve,” Denove said.

It’s not an easy path to make a name for yourself as a plaintiff attorney, Vartazarian admits. There’s a lot more uncertainty and a lot more financial risk, especially for younger lawyers, than a safer career trajectory padded by lower settlements might offer.

Nonetheless it’s a path he’s clearly proud of following and eager to help other attorneys walk, provided they’re willing to put themselves out there to make the connection. If you can match real skill in the courtroom with a palpable passion for the work, he truly believes that will resonate with like-minded attorneys in communities like CAALA.

“People like personality. People like character. People like vision,” Vartazarian said.

Apparently juries do, too.

***

E-mail David Siegel at dsiegel@cvn.com