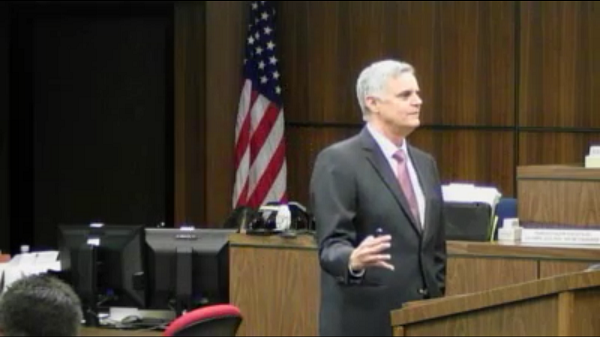

Alex Alvarez tells jurors in closing arguments that his client, Thomas Ryan, was misled by R.J. Reynolds claims that filtered cigarettes were safer to smoke. Jurors awarded Ryan and his wife, Bettye, $21.5 million in compensatory damages Friday afternoon in their suit against Reynolds.

Ryan v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co.

Jurors Friday awarded Thomas and Bettye Ryan $21.5 million in compensatory damages, with an award of punitives to come, after finding R.J. Reynolds liable for Ryan’s chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The decision followed less than four hours of deliberations and found Reynolds 65 percent liable for the COPD that the Ryans claim was caused by tobacco industry marketing that led to Ryan's nicotine addiction. Ryan smoked up to four packs of cigarettes a day for more than 40 years. He ultimately quit smoking in 1997 after being diagnosed with respiratory disease.

The decision followed less than four hours of deliberations and found Reynolds 65 percent liable for the COPD that the Ryans claim was caused by tobacco industry marketing that led to Ryan's nicotine addiction. Ryan smoked up to four packs of cigarettes a day for more than 40 years. He ultimately quit smoking in 1997 after being diagnosed with respiratory disease.

The jury’s compensatory award includes $16.5 million to Ryan and $5 million to his wife, Bettye. The award exceeded the $20 million in total compensatories the Ryans’ attorneys requested in closings Friday.

The verdict capped a two-week trial in which opposing counsel debated whether Ryan could reasonably have believed tobacco industry-sponsored tactics to conceal the dangers of cigarettes. During closing arguments, King & Spalding’s W. Ray Persons, representing Reynolds, told jurors that health warnings everywhere from cigarette packs to television news programs, combined with smoking's effects on Ryan's family members, outweighed any tobacco messaging he may have seen.

Persons noted that Ryan’s father was diagnosed with smoking-related COPD in 1983, but that Ryan did not try to quit smoking until after his father’s death in 1987. "He didn’t try, didn’t make one single effort to quit (prior to 1987),” Persons said. “Full knowledge. If you don’t know by that time, there’s nothing that R.J. Reynolds can do or say that will tell you or convince you that this is a dangerous activity.”

However, The Alvarez Law Firm’s Alex Alvarez, representing the Ryans, argued that Ryan was initially misled as a teenager in the 1950s by tobacco industry marketing, then duped again by false claims that filtered cigarettes were safer to smoke. Alvarez reminded jurors that Ryan began smoking Reynolds’ Vantage filtered cigarettes, believing tobacco industry claims concerning the filters’ safety. “He switched, he thought he was doing something safer, when all of the time (Reynolds) knew it wasn’t true,” Alvarez said. “Vantage is as much, or more, deadly than any other cigarette.”

The decision in this trial follows a mistrial entered in an earlier Ryan proceeding just 15 days ago. On April 2, two Florida Supreme Court decisions found Engle progeny plaintiffs like the Ryans were not required to prove reliance on tobacco industry conduct within the state’s 12-year repose period for fraud. Those decisions overturned controlling 17th Judicial Circuit case law on the subject, prompting Judge Jack Tuter, who presided over that earlier Ryan trial, to declare a mistrial. The current Ryan trial was rescheduled with Judge John Murphy presiding.

Next week: Phase 2, to award punitives, will begin Monday morning.

The physician that diagnosed and treated smoker Phyllis Frazier for the beginnings of the respiratory disease that ultimately led to her lung transplant testified this week about Frazier’s struggles to quit smoking as the disease progressed.

Dr. Steven Shapiro testified that Frazier resumed smoking as soon as possible after a 1991 acute respiratory attack that had rendered her physically unable to smoke. “This is common; I see thousands of patients who smoke. As (Frazier) felt better and she could breathe again, she went back to smoking,” Shapiro said.

Shapiro diagnosed Frazier, a smoker for more than 30 years, with symptoms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 1991. However, Frazier did not successfully quit smoking until a year later, after several attempts using smoking cessation methods ranging from nicotine gum to patches.

Despite quitting smoking, the disease’s effects became so serious that she underwent a lung transplant. She ultimately died in 2012 from skin cancer that spread to her brain. Her attorneys argue that drugs Frazier took to combat her body’s attempt to reject her new lungs compromised her immune system, causing the cancer to spread. Frazier’s daughter, Tina Russo, is suing Philip Morris and R.J. Reynolds, claiming the tobacco manufacturers fueled the nicotine addiction that led to Frazier's respiratory disease.

Referring to records of Frazier’s treatment, Shapiro told jurors that, despite the disease's progression, Frazier described a “driving urge to smoke” that rendered quitting difficult.

However, the defense argues that Frazier was not interested in quitting smoking until shortly before she successfully stopped. And on cross examination Monday, Shapiro acknowledged that Frazier waited months before ultimately filling a prescription for nicotine gum that Shapiro had given her in 1991.

“If (smokers) do not want to stop, nothing I say or do will make a difference,” Shapiro said.

Next week: The case is expected to go to the jury by the end of next week.

Arlin Crisco can be reached at acrisco@cvn.com.

Our weekly review is curated from our unequaled gavel-to-gavel coverage of Florida's Engle progeny cases.

Not a subscriber?

Click here to learn more about our expansive tobacco litigation library.