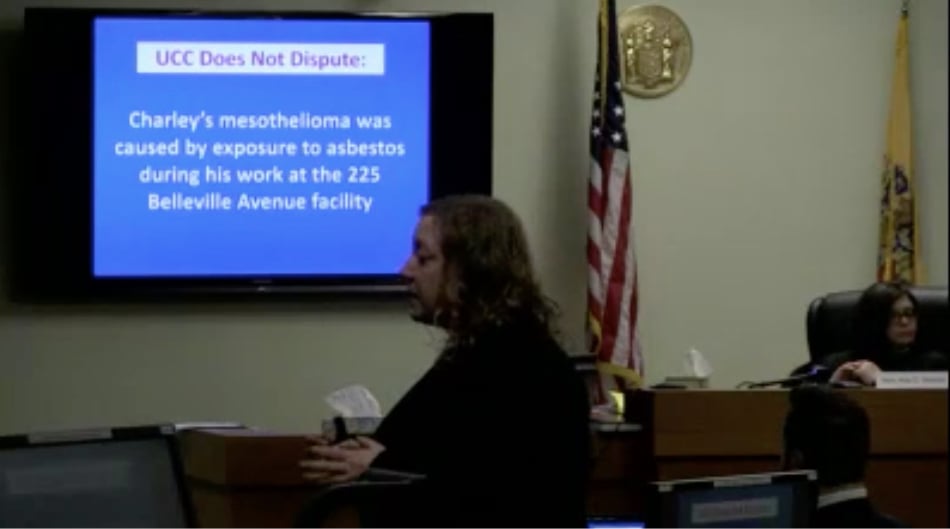

CVN screenshot of plaintiff's attorney Amber Long delivering her opening statement

New Brunswick, NJ - A New Jersey state court jury heard opening statements on Monday in a lawsuit alleging that decades of exposure to Union Carbide’s asbestos products caused a man’s fatal cancer.

Plaintiff Thomasina Fowler sued Union Carbide following the death of her husband, Willis “Charley” Eddenfield from pleural mesothelioma in 2011. Fowler, represented by the New York-based firm Levy Konigsberg LLP, accuses Union Carbide of failing to adequately warn workers about the serious health risks associated with asbestos.

Eddenfield worked at an industrial site in Bloomfield, New Jersey operated by the now defunct National Starch and other companies from 1954 until 1994. He frequently retrieved asbestos-containing materials from a “mill room” to later use in products like sealants, gaskets and adhesives and supposedly came into contact with thousands of pounds of asbestos over the years.

Union Carbide, represented by defense powerhouse Lewis Brisbois Bisgaard & Smith LLP, argues that there is no evidence proving Eddenfield was exposed to asbestos products purchased from the company, maintaining that the only witness to testify about Fowler’s work with asbestos stated he saw him using another brand.

The full trial is being webcast gavel-to-gavel by Courtroom View Network.

Fowler’s attorney Amber Long told jurors during her opening statement that because Eddenfield died before he could be deposed she would rely largely on circumstantial evidence to prove he was exposed to Union Carbide’s products. Long said she would present documentary evidence like invoices to prove Union Carbide’s asbestos was present at the National Starch worksite, along with testimony from two of Eddenfield’s former co-workers.

“I think you’re going to find that the circumstantial evidence is overwhelming that Charley was absolutely exposed to Union Carbide’s asbestos,” Long told the jury.

She described a worksite where asbestos dust in the air was a common occurrence, but claimed that for years workers wore only paper dust masks instead of respirators due to inadequate warnings provided to purchasers and workers by Union Carbide. She characterized the warnings Union Carbide did provide as meeting only the bare minimum standards that were legally required, despite the company knowing that much stronger warnings were needed to adequately protect workers.

“Compare what UCC knew with what they told Charley, and you’re going to see there was a big difference,” Long said.

Union Carbide attorney Scott Masterson told jurors that while Eddenfield did contract mesothelioma from exposure to asbestos, that there was insufficient evidence to hold Union Carbide liable for his death.

Eddenfield claimed exposure to a type of chrysotile asbestos called Calidria, but Masterson told jurors they would hear expert testimony stating that there is no convincing scientific evidence linking Calidria exposure and pleural mesothelioma.

Masterson walked jurors through the evolution of science’s understanding about the health risks of asbestos during the second half of the 20th century, maintaining that warnings provided to National Starch and their workers by Union Carbide were consistent with the medical and scientific knowledge available at the time. He said National Starch should be responsible for decisions like not providing workers with respirators.

“UCC told them everything that they knew at the time about asbestos,” he said.

Natural Starch’s successors were originally included as defendants in Fowler’s complaint, but only Union Carbide remained when the case went to trial.

Masterson also suggested that the circumstantial evidence the plaintiff’s team relied on would actually prove the defense’s case, telling jurors that the only specific brand of asbestos products Eddenfield’s co-workers testified about seeing him use was from Johns Mansville and not Union Carbide.

A New Jersey appeals court revived the long-running case after Judge Ana Viscomi, who presides over New Jersey’s consolidated asbestos docket, granted Union Carbide’s motion for summary judgment in 2015 based largely on the fact that none of Eddenfield’s co-workers could specifically recall seeing him use Union Carbide’s asbestos products.

“While UCC presented evidence other companies provided asbestos during this period and no witness could unequivocally link UCC's asbestos to decedent, plaintiff presented evidence UCC provided over 40,000 pounds of asbestos to the facility over a twelve-year period while the decedent worked handling asbestos,” the appeals court wrote in their opinion reversing Viscomi’s decision.

The full trial, which could last up to four weeks, is being webcast and recorded gavel-to-gavel by CVN. Besides the current trial, CVN subscribers can also view gavel-to-gavel video of dozens of other asbestos and product liability trials from New Jersey and throughout the United States in CVN’s one-of-a-kind online trial video archive.

The case is captioned Thomasina Fowler, individually and as administrator and administrator ad prosequendum of the estate of Willis Edenfield v. Akzo Nobel Chemicals Inc., et al., case number L-4820-11 in Middlesex County Superior Court.

Email David Siegel at dsiegel@cvn.com